I defend my dissertation on July 7. "Reforming (Men of) Letters: English Language Reform and the Formation of English Literary Identity (1540-1660)." Oh yeah, it's a gripping read.

Shall I bother to translate? Well, it goes something like this: we are accustomed today to thinking of English as a literary language, capable of communicating compelling ideas in an inventive, if not entertaining, manner. The English person "of letters" is also a familiar figure: whether highly knowledgeable about the language and its literature, as with university professors, or contributing to its literary tradition, as do contemporary poets, essayists, and novelists, men and women who study the English language and know what things are possible with it form a pretty select group.

(In many respects, the latter phenomenon follows from the former: that is, the esteem we tender our teachers and writers flows from the value we assign our language, our belief that English is sufficiently worthy that those who make a profession of it deserve our admiration and respect. And it follows inversely as well, that when contemporary writers and university English departments come under fire, it is usually because these presumed arbiters of language and literature are thought to have reneged on their custodial obligations. It's an absurdly tough racket.)

But to "men of letters" in the beginning of the sixteenth century -- men trained in the literary classics of ancient Greece and Rome -- none of this would have made any sense. At that point in time, English was thought to be rude, crude, and unfit for transmitting literature or learning. You learned the vernacular by happenstance, at home and through daily conversation, and no manuals existed (grammars, dictionaries, etc.) to teach "correct" or "proper" forms of the vulgar language, the (emphatically female) mother tongue.

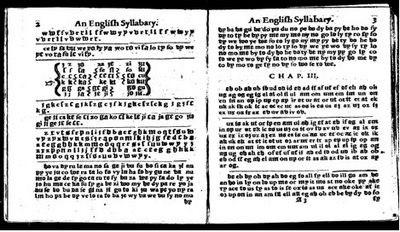

The first such attempt to regulate English took place during that century, and while we are also accustomed to thinking of sixteenth-century writers such as Shakespeare as icons of English literary culture, benchmarks of vernacular accomplishment, part of their task in electing to write English literature was to reform both the form -- the spelling, grammar, syntax, and vocabulary -- and the reputation of the language itself. My study shows what part the first spelling manuals and elementary textbooks played in their efforts, to give rise to a distinctly English literary identity -- a man of English letters, and an occupation worthy of social esteem.

The first such attempt to regulate English took place during that century, and while we are also accustomed to thinking of sixteenth-century writers such as Shakespeare as icons of English literary culture, benchmarks of vernacular accomplishment, part of their task in electing to write English literature was to reform both the form -- the spelling, grammar, syntax, and vocabulary -- and the reputation of the language itself. My study shows what part the first spelling manuals and elementary textbooks played in their efforts, to give rise to a distinctly English literary identity -- a man of English letters, and an occupation worthy of social esteem.

With esteem in mind, I thank those of you who have gotten in touch to say you're enjoying la Jardiniere. Virtually all of you have wondered "where I find the time," what with dissertations to finish, houses to buy and sell, children with birthdays and unfortunate injuries, processing the family's immigration to Canada, and, of course, maintaining the garden. To be honest, the blog has become my down (you could even say "me") time. Besides the Bee last week, I can't remember the last time I watched television (actually, I think it was that American Idol finale). I only just cracked open a new book last night -- Philip Roth's American Pastoral.  I chose that book in particular because it is one of the many novels selected in the recent NYTimes Book Review survey (of the best novels of the past twenty-five years) that I haven't read. It is a graduate school parlor game to confess what classics in English (or American) literature you haven't cracked. (Erm, "Call me Ishmael?" That's about it for me in that one.) No doubt I am susceptible to the charge of being an "out of touch" academic, my head buzzing more about middle English alphabets than the Pulitzer prize winners published in my own lifetime.

I chose that book in particular because it is one of the many novels selected in the recent NYTimes Book Review survey (of the best novels of the past twenty-five years) that I haven't read. It is a graduate school parlor game to confess what classics in English (or American) literature you haven't cracked. (Erm, "Call me Ishmael?" That's about it for me in that one.) No doubt I am susceptible to the charge of being an "out of touch" academic, my head buzzing more about middle English alphabets than the Pulitzer prize winners published in my own lifetime.

The role of the academy came up several times in critics' discussion of the Book Review's list (on a dialogue on the NYTimes online, on the Charlie Rose show, on NPR, etc.; really, that Sam Tanenhaus was everywhere), and suffice to say, it often did not come off well. The programs illustrated the internecine conflict that unfortunately exists among those "of letters" in contemporary society, which is to say, between the academic literary profession and the guild of literary journalists.

If I can say something in the academy's defense (and I should divulge that my grad school compatriots can attest that when it comes to the "let's slag off academia" parlor game, I have few peers), it would be to foreground the role and importance of peer review in the profession. Such a process has its undeniably deleterious, and frequently publicized, effects: the botched tenure cases (for many critics, tenure itself), the rampant politicking, and the way academics converse in a language little resembling spoken English (see my own dissertation title).

As in any profession, such as law or medicine, roofing or plumbing, jargon enables practitioners to communicate with a degree of specialization befitting their mutual expertise; and while the specialized language functions to exclude those who have not passed through the requisite, and torturous, professional gauntlets -- an effect especially denounced in literary studies, by those who suppose it our task to make literature more accessible, not less -- it also, at some level, testifies to the good faith effort of many such professionals, and I am including myself here, to arrive at just the right, if admittedly abstruse, words to communicate complex ideas. In my profession, for better and for worse, I have to argue and defend my points of view and the words I choose to express them ("why 'formation' and 'identity'" in my title, for example -- I expect these questions at my dissertation defense, and must come prepared to answer them).

Literary critics are no less committed to their craft, and are subject to the critical, and often punishing, review of the general interest reader (visit The Fray on Slate magazine to see some real humdingers). But the selection and transmission of ideas in literary journalism is guided, some might say misguided, by special interests as well, i.e., those of the general marketplace. After all, editors have got to move mags and increase downloads to keep the whole operation afloat, and it is a tough racket deciding which ideas are worthy, and which will sell. But the very ubiquity of (Times Book Review editor) Sam Tanenhaus signaled that the Times survey was as much about promoting the Times Book Review as it was an occasion to discuss what makes a great book.

Indeed, what did not come out in the NYTimes discussions, that should have, is the role that mass marketing machines play in the construction of contemporary literary taste. Have we -- academics, critics, the general interest reader -- had any say in our three-year inundation by The Da Vinci Code? If literary critics wish to claim from the academy a certain jurisdiction over language and literature, I am more than glad to cede them the power to counteract, or merely complicate, the considerable clout of publishing house ad copy. Both academics and critics suffer in the popular imagination: if academics are thought to be "out of touch," critics are often said to be pretentious and self-aggrandizing (think of the reader who claims "never to listen to critics"). Would that we men and women of letters could talk to one another, and to the general readership, more effectively, in keeping with our mutual interest in our tongue.

I started this blog in that very spirit, and because I wanted to transmit ideas about language in contemporary culture, but did not have the time nor the patience to sell my ideas to editors, who weren't buying (and being a grad student for so many years, I am used to giving my ideas away for free!). I have done freelance work before (in graphic design) and know that in the beginning, ninety percent of your time is devoted to hustling new work. Nah. I've got a job (amen). I'd rather focus on developing the ideas. Many of them -- my pieces on spelling, for example -- admittedly originate from my scholarly work. And I know that my prose suffers from my academic training, that it is too wordy and esoteric. La Jardiniere allows me to practice simplifying my ideas and how I should express them, in hopes that I may cross that bridge between academia and general criticism (and maybe make a buck -- I should say a "loonie" -- from it someday). Thanks for reading, and for all of your feedback. Merci.

P.S. And I should say that I am enjoying the Roth -- the man knows his way around a complex sentence!

1 comment:

The NYT choices of best American fiction published in the last 25 yrs was interesting to me, for many reasons -- I was delighted to find that the 3 books I am teaching in my Historical Fiction class published in the last 25 years are on the list and so could say to my students "look! these are good books! everyone says so!" But really this wasn't necessary, as everyone respoded positively to Beloved, The Things they Carried, and the Prologue to Underworld. One student did explain how exasperated he was at the beginning of Beloved when he realized it was going to be a painful novel about slavery. "I just didn't want to read it," he said. "too depressing". If I had chosen my top book, it would have been Underworld -- not because of its substantial heft, as several critics have suggested, but because the Prologue (previously published as a short story, "Pafko at the Wall") is what I consider to be the best piece of American writing in the last 25 years. The rest of the book is uneven and, if I may say so, a bit TOO epic. As for Philip Roth, who received votes for various books -- such a beautiful writer, but such a pig. It would have been hard for me to vote for a writer who I feel is fundamentally such a misogynist -- Maybe I could have voted for Portnoy's Complaint (which did not appear on the list), a book that escapes that charge simply because it's the point of view of an adolescent, and everyone's thoughts are offensive at that age. I don't have a problem with Amis's The Rachel Papers for the same reason. The Sportswriter is problematic for reasons similar to those I assign Roth-- Ford is a beautiful writer. But his character's offensive assessmemts of women run so deep that the writer seems to be culpable as well. I know many people will say it's not fair to condemn a writer for his character's views, but in the case of Roth his attitude toward women is consistent throughout a large body of work, and through many characters. And, if I do say so, sometimes you just feel confident that you can read a writer's hangups. Like: Jonathan Franzen has issues about being from the midwest. It was one of the things that bothered me throughout the Corrections. Get over it! There are tacky, provincial people throughout the tri-state area too!

As for my choice for a book to read that I hadn't (that received attention on the NYT list), I'm going for Updike's Rabbit books. From what I've heard from others, he's not misogynist -- he's a plain misantrope. That seems like a healthy attitude to me!

Post a Comment