Do you do Sudoku? Who doesn't these days? Sudoku has replaced time-honored newspaper pastimes and become a daily fix for legions of broadsheet readers. If you think about it, the pleasures of Sudoku are not far removed from those of the Crossword and the Daily Jumble; Sudoku merely trades letters for numbers. Whatever diversion you indulge in, each puzzle promises as the end of your effort one delightfully satisfying solution (huzzah!).

Do you do Sudoku? Who doesn't these days? Sudoku has replaced time-honored newspaper pastimes and become a daily fix for legions of broadsheet readers. If you think about it, the pleasures of Sudoku are not far removed from those of the Crossword and the Daily Jumble; Sudoku merely trades letters for numbers. Whatever diversion you indulge in, each puzzle promises as the end of your effort one delightfully satisfying solution (huzzah!).

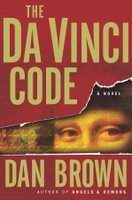

Reuters has an article out in which the author, Arthur Spiegelman, tries to account for the astonishing success of Dan Brown's novel, The Da Vinci Code [http://news.yahoo.com/s/nm/20060515/en_nm/leisure

_davinci_success_dc_4]. While the article notes the role that Doubleday's marketing push may have played (e.g., "They sent out 10,000 advance copies of the book to booksellers, critics, media and advertising people -- a gigantic number for such an undertaking"), Spiegelman otherwise parrots criticism already in circulation, analyses which center on the religio-historical claims advanced by the novel’s plot (i.e., that Jesus Christ married Mary Magdalene, and has living human heirs).

Allow me some leeway to sound litsy-critsy, and suggest that critics have been reading Brown's novel too literally -- at the level of plot -- and yet not literally -- at the level of the letter -- enough. For, like the Crossword and the Daily Jumble, what do codes and ciphers do but challenge readers with an alphabetical riddle, to yield one final, incontrovertible, and again satisfying solution? The Da Vinci Code is literary Sudoku, a novel that poses a series of puzzles and prints their solutions on the next page, to legions of readers' vast satisfaction.

Holy Scrabble, Batman, you say, but can we dispense entirely with delicious conspiracy theories? Not entirely, my young crimson squire.

The "controversy" surrounding The Da Vinci Code concerns the alleged existence of a centuries-old, world-wide cover-up of the facts of Jesus Christ's life and death. For many, the fictive claim that Jesus procreated amounts to sacrilege, if not heresy, and threatens the spiritual bedrock of the Christian church. As Spiegelman reports, Nick Owchar, deputy editor of the Los Angeles Times Book Review, sees in the claim potential reason for the book's appeal, musing that "The book challenges the familiar story of Jesus's life but . . . also challenges ideas that for a vast number of Americans are a familiar part of their faith [,] and people enjoy toying with things that are subversive." No doubt readers enjoy novels in which the narrative departs from -- is both based on and "toys with" -- the artifacts of the everyday, as the latter serve as "familiar" touchstones from which the reader may venture into escapist fiction.

We need go no further than today's front pages, however, to entertain conspiracies and cover-ups that threaten the security of Western ideals. Uranium in Niger? No. Saddam Hussein's links to al Qaeda? Nope. Weapons of mass destruction? Sorry. Once we grant that playing word games is central to the experience of reading The Da Vinci Code, we can attribute its conspicuous success to the fact that it not only solves the series of speciously knotty problems it poses, but also administers a mental salve to Americans fatigued from deciphering U.S. foreign policy (huzzah!).

The advance marketing push Spiegelman mentions took place in February of 2003, after President Bush's State of the Union speech that year (in which he made several of the claims, since disputed, above). Doubleday issued The Da Vinci Code on March 18. The United States invaded Iraq on March 20. __The Da Vinci Code’s reign atop the New York Times Best Sellers list coincides, nearly to the day, with the U.S. occupation of Iraq.__ Why did it succeed? Because The Da Vinci Code delivers the clarity and resolution the President and his henchmen claim to offer, but deny.

Who hasn’t scratched their head over some of these brainteasers from Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld?

¶ "I would not say that the future is necessarily less predictable than the past. I think the past was not predictable when it started."

¶ I believe what I said yesterday. I don't know what I said, but I know what I think, and, well, I assume it's what I said."

Hmm. Let me see if I can work that one out in the margin. And those anacronymic WMDs, Secretary Rumsfeld, what about them?

¶ "We know where they are. They're in the area around Tikrit and Baghdad and east, west, south and north somewhat."

¶ "There's another way to phrase that and that is that the absence of evidence is not the evidence of absence. It is basically saying the same thing in a different way. Simply because you do not have evidence that something does exist does not mean that you have evidence that it doesn't exist."

I see. But if, like me, you were still confused by the Secretary's position on empiricism, he clarified with the following treatise on epistemology:

¶ "Reports that say that something hasn't happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns -- the ones we don't know we don't know."

Ahh, yes. A modern-day Socrates.

You might say that reading these quotes is not unlike reading the chapters of Dan Brown's novel. Short and pithy (in their own way), each chapter in The Da Vinci Code ends with a mini-cliffhanger, leaving you wanting more information, and pushing you to reach the conclusion. The press conferences in which Rumsfeld issues these puzzlers are sadly ongoing, however, making for a never-ending serial in which the arch-villain of the story (Osama bin Laden) is never caught, and the whodunnit (who got us into this war, and why?) never solved. It is too much to desire a conclusion in which we see President Bush praying over the tomb of last soldier killed, just as we see Tom Hanks kneeling over the inverted Pyramid at the Louvre (in the marketing photo from the upcoming movie).

Instead, we puzzle out the President's own Daily Jumble:

¶ "The war on terror involves Saddam Hussein because of the nature of Saddam Hussein, the history of Saddam Hussein, and his willingness to terrorize himself."

¶ "I just want you to know that, when we talk about war, we're really talking about peace."

¶ "Our enemies are innovative and resourceful, and so are we. They never stop thinking about new ways to harm our country and our people, and neither do we."

So dark the con of man, indeed.

Critics such as Laura Miller (at Salon) have described The Da Vinci Code as "cheesy," by which (I think) she means that the novel panders to an unsophisticated readership by using stale and shopworn literary techniques. As Dan Brown acknowledged in the pseudo-memoir he presented as his deposition in his UK plagiarism trial, The Da Vinci Code does not aspire to be great literature. Brown's confessed delight for codes and ciphering underscores his pedestrian aim merely to write a ripping read. Like the piece of pulp fiction in which they appear, the novel's codes offer unrefined readers both the illusion of a literary challenge -- the chance to play codebreaker (or "symbologist"), and try out solutions in the margins of their mind -- and the comforting security of explanation. We are promised no such comfort or resolution from our cryptic US President: "I'm the commander — see, I don't need to explain — I do not need to explain why I say things. That's the interesting thing about being president."

In writing a book whose plot challenges ideas that Christianity holds sacred, Dan Brown (a religious man himself, as I understand) countenanced the primacy of faith in Western culture, effectively giving it some good PR. After all, Jesus himself knew the value of controversy for good publicity, and while Brown may be guilty of hackneyed prose, I doubt that many of his Christian readers felt their beliefs were shaken by his book, and many may have found them reaffirmed. That's the interesting thing about being a "cheesy" writer of pulp fiction. Nobody gets hurt.

But if we weigh the imagined effects of Brown's sacrilegious plot against the alarming prospect that the US President claims to act on God's will -- "I trust God speaks through me. Without that, I couldn't do my job" -- it is not implausible to trace the appeal of Dan Brown’s novel about religious codes to the faith-laced mystifications of President Bush, as the escapist pleasures offered by the one divert Americans from the tragedies accruing from the other. The novel's recent paperback release, together with the Sony film (directed by Ron Howard and starring Tom Hanks, each Hollywood symbols for reassuring sincerity), promise that The Da Vinci Code will remain indefinitely, like the occupation of Iraq, in the American public consciousness. God help us -- Dan Brown can't -- if the latter does not yield a satisfactory resolution.